Open source BOM management

July 2025

20:20

Since graduating from university I’ve gotten more and more into embedded software development. This has even spilled over into designing PCBs (printed circuit boards) for my embedded devices to sit on.

Initially I had assumed that the leap from software to hardware design would be insurmountable without any formal education but it turned out to be quite enjoyable. It turned out that the problem I’d be facing wasn’t a technical one, but of an organisational nature.

Designing circuits

Designing circuits turned out to be a lot like software development. Or at least I managed to force it to become similar to how I develop software.

Modular parts or blocks, which I could share between circuits needing similar functionality sounds a lot like DRY. Avoiding complexity by only including the absolute bare minimum that I could get away with sure sounds like KISS. And so I charged forwards into the world of power electronics, sensors and Bluetooth communication, armed to the teeth with sort-of applicable design principles.

I ordered PCBs, parts and went to town with soldering paste, stencils and a soldering iron to realise my new creations. And that is where the problems began.

Parts and components

Each circuit could be composed of up to ~40 different parts that needed to be mounted on the board. And since I had been so clever as to share designs between boards I could even use parts from the stocks of one circuit board to build another design if it was missing any parts.

One day, when I was looking to build Battery manager V1.2 and was scrambling through box after box of components I realised that I couldn’t find the appropriate step-down converters needed. In fact, I didn’t even know if I had any left. And for that matter, did I have any 10 kΩ resistors left?

The overlapping component usage had left me with no actual idea of my inventory. There was no way of knowing how many of each circuit design that I could actually build and ordering new parts was just as big of a nightmare since couldn’t get a grip on what parts I’d actually need.

Keeping stock of components for my designs was a new problem I hadn’t considered. If I want to build a version of my latest pdf-reader on a new computer, I just compile it. There’s no need to check for complex, interwoven dependencies between it and other software I’d written before constructing the design, in software you can just do it.

The solution

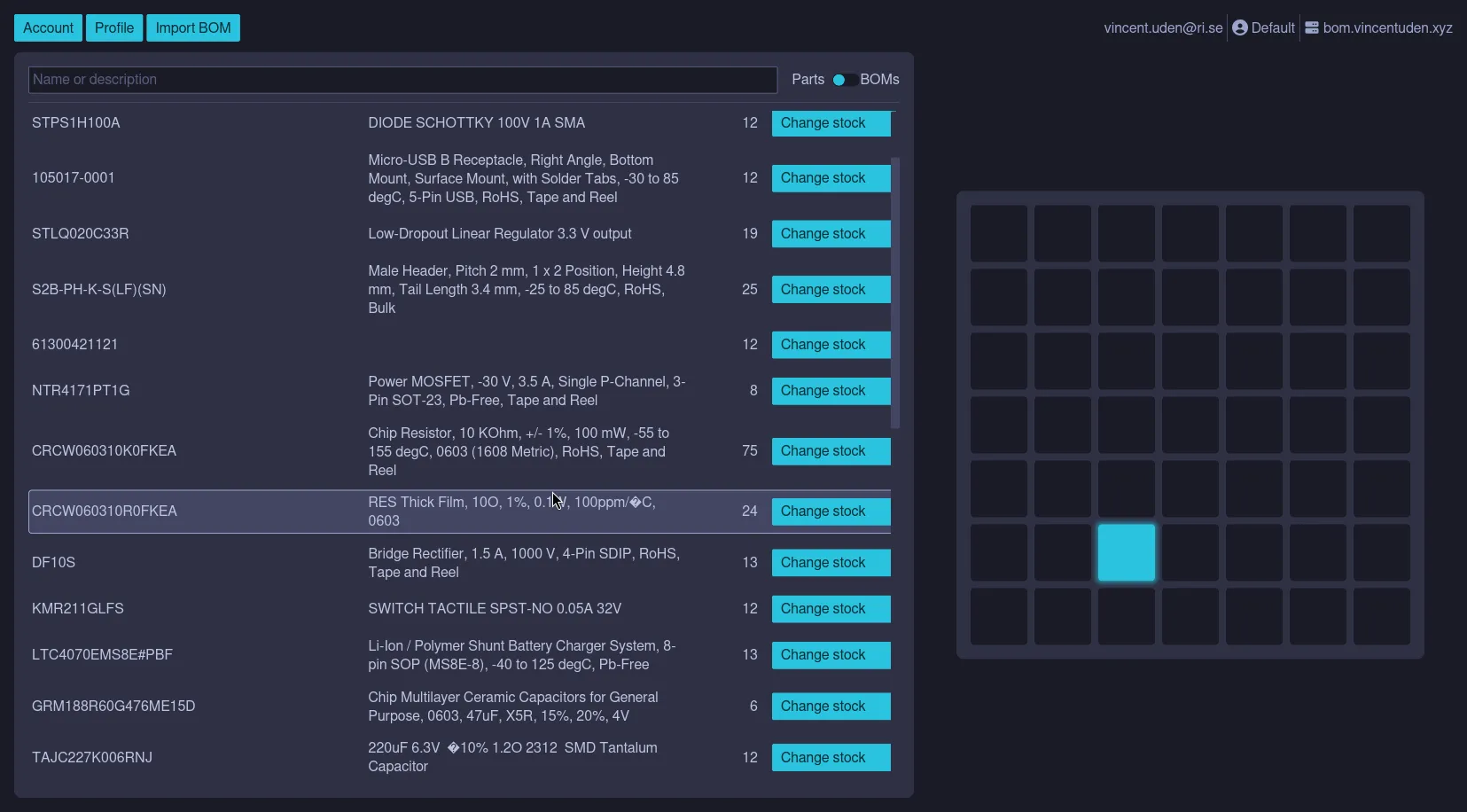

Having the hammer of software development at my disposal, organising electrical components was looking a lot like a nail. The resulting program consists of parts, a panel and a grid.

As the mouse hovers over each electrical part, it’s position in the grid is highlighted on the right. Why a grid? What does it represent? A physical, 3D-printed grid storage system of course.

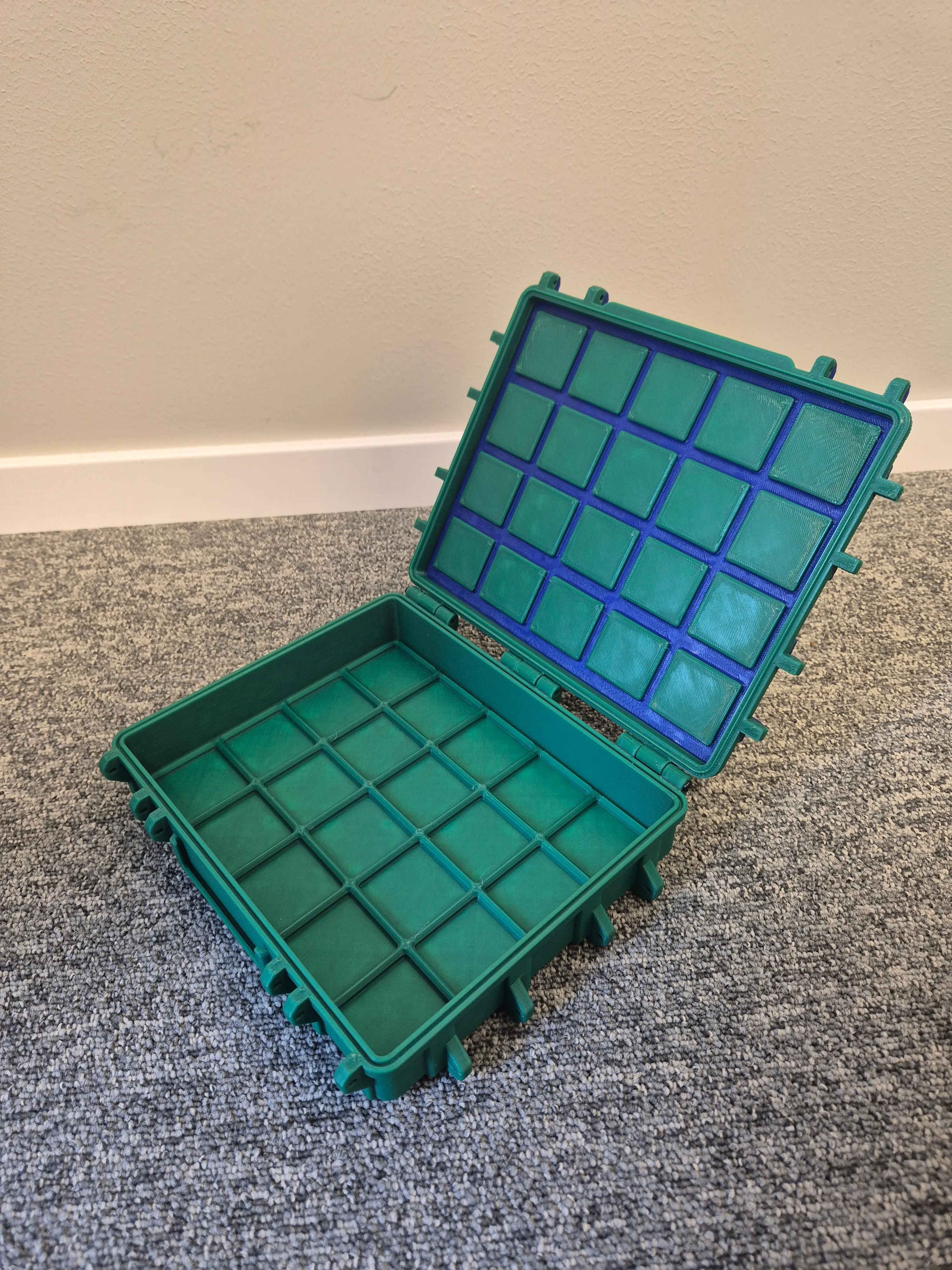

The grid is part of the modular, open-source storage system Gridfinity. In particular the parts I used were generated in the OpenSCAD-powered Gridfinity Generator.

This parametric interface allowed be to print bins for each component and a compatible baseplate for them to stand on. Among other models it also allowed me to generate .stl files for a portable carrying box (Rugged box) which I use to transport the parts from my cabinet to the electronics lab for assembly.

Bins

As could probably be derived from the mixed colouring of my grid, I printed the parts from filament I had laying around, thus the slightly stochastic look.

To label each bin I wrote a typst file which automatically lays out each component name on an A4 paper with guides for where to cut. The only input is a list of component names whose labels shall be printed

#let names = (

"ERF1002",

"TMK107B7105KA-T",

"STPS1H100A",

"105017-0001",

"...",

)ECAD to BOM

Having a mapping from a physical grid of components to a digital database of their count seems useful but isn’t enough to provide a satisfactory user experience.

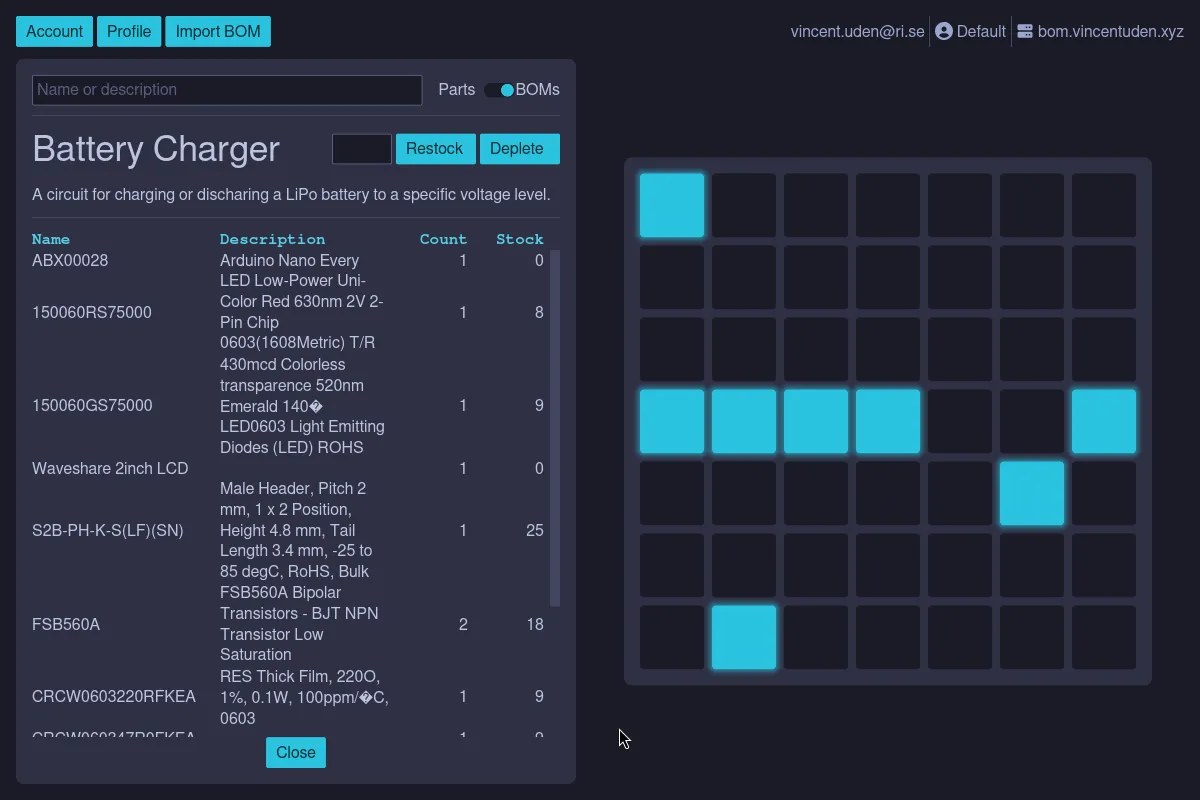

The most important part of the software isn’t visible until the left panel is switch from Part Search to BOM Search. In BOM (bill of materials) mode, I can search for entire sets of parts belonging to circuits I’ve designed. These are of course imported straight from the csv export of Altium Designer where I design them.

Opening a BOM shows the location of all components needed to assemble it and allows for batch stock management. This shows me which bins to place in the aforementioned rugged box to be brought to assembly.

Future work

While the software is currently perfectly usable, I should know since I use it frequently, there is still room for improvement. Key features I’m looking to implement in the future are:

- BOM export for bulk purchases at Digi-Key or Mouser

- Settings for the grid, not everyone (or me in the future) is going to have a 7x7 grid layout

- Grid-based search. Right now the search is one way, from the left panel to the grid. A user should be able to query the grid for the component it is supposed to contain

I had a lot of fun building the software itself. Native GUI applications have always implied more pain than necessary for me, until I found iced which empowered me to build this program among a few others.

Before arriving at the GUI I also wrote a completely standalone CLI version of the program which has been of great use for testing. The two front end are available in pcb-parts-client and the server is available at pcb-parts-server. Which leads me to the final piece of future work:

- Write a blog post about making the software itself, it’s architecture and development strategies I employed to minimise risk at every step